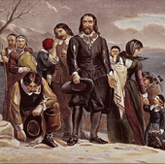

| Landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock in 1620. 19th century by Currier & Ives. Credit: Giraudon / Art Resource, NY. |

|

|

|

|

|

o most Americans, the word “thrift” has a decidedly quaint ring to it. It’s something grandparents talked about, a virtue Victorian-era social reformers extolled, a practice that harks back to a time that no longer exists. David Blankenhorn, a leading traditionalist, is looking to change all that. o most Americans, the word “thrift” has a decidedly quaint ring to it. It’s something grandparents talked about, a virtue Victorian-era social reformers extolled, a practice that harks back to a time that no longer exists. David Blankenhorn, a leading traditionalist, is looking to change all that.

“Thrift isn’t just about ‘saving for a rainy day’. It is actually a moral stance about one’s relationship toward the material world,” says Blankenhorn, the Founder and President of Manhattan’s Institute for American Values. “The ethic of thrift is inseparable from the ethic of doing good in the world… [Sir John] Templeton is a living example of that.”

Blankenhorn is spearheading the Thrift and American Culture Project, a two-year effort that is commissioning 32 scholarly papers on the subject. The Project, funded by the Foundation, has an academic thrust, but Blankenhorn imbues it with an infectious, evangelistic fervor. He seeks nothing less than to restore thrift as a national value: “There was a time when it was taught to children and important people had something to say on the subject.”

The economic dimension of thrift is most often thought of in terms of savings and this garners the most media attention—as it should, say experts. “After a long period of stability near 11 percent of income, the net national saving rate began to decline in the early 1980s and, in 2005, it reached an astounding low of only one percent of national income,” Barry P. Bosworth, a Senior Fellow in Economics at the Brookings Institution testified in 2006 before the U.S. Senate’s finance committee. Such low savings rate means that U.S. industry turns abroad for the capital necessary to grow and innovate, potentially turning Americans’ lack of thriftiness into a national security issue. The current U.S. economic quandary of dependence on foreign capital, low savings rates, unsustainable domestic consumption and a widening gap between rich and poor may prove to be a recipe for disaster—but not for the reasons held by conventional wisdom.

“People don’t seem to be resentful of the rich,” says a Thrift and American Culture Project scholar, Cornell University economist Robert H. Frank. “They won’t snap because they are angry at the rich. They’ll snap because they’re filing for bankruptcy.”

But it is a mistake to view thrift purely in terms of accumulating wealth, say Thrift and American Culture Project participants. As its weight grew in popular culture in 19th century America, “thrift was a part of a constellation of other virtues that are part of the High Victorian period and later. The temperance movement, for example, associated thrift with sobriety,” comments Joshua J. Yates, the Thrift and American Culture Project’s principal investigator and a research assistant professor at the University of Virginia.

Two Thrift and American Culture Project scholars are going even farther back in American history to examine the theological roots of thrift, looking at Puritans in both colonial America and 17th century England. As Middlebury College professor James Calvin Davis explains, the Puritan notion of thrift was quite broad, incorporating conservation and moderation, and was a “reaction to the cultural excess in England at that time.” Davis cites the work of English Puritan Richard Baxter who gave a detailed theological explanation, grounded in thrift, for why “elaborate preening” and excessive attention to one’s appearance were an affront to God.

One of the key aims of the Thrift and American Culture Project is to distill the scholarly work on thrift into a 70-page report designed to generate national debate and discussion on the issue. By the middle of 2007, the Thrift and American Culture Project will conclude with a conference in Washington D.C. “Our goal,” says Blankenhorn, “through scholarship and research, is to put the subject of thrift back into public debate.”

www.americanvalues.org

|

|

|