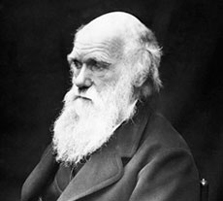

he

ambitious idea of publishing all the letters of Charles Darwin was originally

conceived in 1974 by Frederick Burkhardt, an American scholar; the project

he founded is now based at

University of Cambridge in the UK. Since then,

the Darwin Correspondence Project has doggedly pursued its purpose of

publishing all 14,500 surviving letters in 30 volumes by 2025. From late

2006, however, this work has been supplemented by a program funded by

a $1.1 million grant from the Foundation to create a new web-based resource

on “Darwin and Religion.”

Out of the overall canon, all of Darwin’s letters relating to religious

themes will be selected for online publication, accompanied by contextual

material, notably including contributions from a wide range of experts

involved in current debates about science and religion. Dr. Alison Pearn

and Dr. Paul White, who are directing the program at University of Cambridge,

describe the progress of the project.

“We have electronic transcripts of all of the letters that we know about,”

says Pearn, “and this July volume 16 of the correspondence series main

edition will be coming out, which takes us over half way.” But there

has been some delay in getting the website discussion forum online. “There

are issues over how you would moderate it,” she explains. The problem

is staff time: there are eight staff members in the UK, but not all are

full-time.

Another part of the grant program is very much up and running. This is

a highly successful dramatization of the correspondence between Darwin

and his friend Asa Gray, Harvard professor of botany and a devout Presbyterian.

“We had a premiere public performance in Cambridge, in the UK, in March

2007,” says Pearn, “and we discovered there was a strong desire among

the academic community to have a shorter version we could take to conferences.”

When the drama was taken to America, Asa Gray’s alma mater was understandably

among the academic venues that welcomed it. “The strongest interest in

putting it on came from Harvard and MIT,” reports Pearn. “We’ve already

been asked to take it back again to Cornell, and Boston University would

like to have it, also a number of conferences.” Consideration is being

given to a longer tour of the United States, visiting colleges and large

congregations, as well as the possibility of a week-long production next

year during the Darwin Centenary celebrations at Cambridge.

Both elements of the “Darwin and Religion” program are intended to dispel

misunderstandings about Darwin’s relationship to matters religious. “Those

with extreme views on both sides of the current debate characterize Darwin

as a champion of science against religion,” says her colleague Paul White.

“The main point to make, I think, is that he was rarely dogmatic about

anything. He regarded personal belief as just that—personal—and generally

regarded science and faith as applicable to different areas of human

experience.”

Does the correspondence throw further light on Darwin’s beliefs, or non-belief?

“It appears from a close study of the correspondence that his beliefs

were not static, but neither did he simply move steadily from a position

of faith to a position of no faith.” The issues that the program, and

eventually the website, chiefly address are the debate over design in

nature, Darwin’s personal beliefs, the breadth of religious belief in

Darwin’s day, the implications for ethics of Darwin’s theory, and the

manner in which religious debate was conducted in the period when Darwin

lived.

It is expected these issues will also be addressed in the public prize

essay competitions being held annually as part of the grant program for

the next three years. The first winner will be announced in summer 2008.

What is the big question that dominates the issue of Darwin and religion?

Pearn and White are in no doubt: “I think ‘Who was Darwin?’ is the one

we are best placed to answer—using his correspondence to reveal his humanity

and to put him in the context of his time and his own nature.”

he

ambitious idea of publishing all the letters of Charles Darwin was originally

conceived in 1974 by Frederick Burkhardt, an American scholar; the project

he founded is now based at

he

ambitious idea of publishing all the letters of Charles Darwin was originally

conceived in 1974 by Frederick Burkhardt, an American scholar; the project

he founded is now based at  University of Cambridge in the UK. Since then,

the Darwin Correspondence Project has doggedly pursued its purpose of

publishing all 14,500 surviving letters in 30 volumes by 2025. From late

2006, however, this work has been supplemented by a program funded by

a $1.1 million grant from the Foundation to create a new web-based resource

on “Darwin and Religion.”

University of Cambridge in the UK. Since then,

the Darwin Correspondence Project has doggedly pursued its purpose of

publishing all 14,500 surviving letters in 30 volumes by 2025. From late

2006, however, this work has been supplemented by a program funded by

a $1.1 million grant from the Foundation to create a new web-based resource

on “Darwin and Religion.”