here

and when did spirituality among humans have its beginning? Was there

a Big Bang moment for the metaphysical as well as the physical world?

There is insufficient data as yet to determine such a hypothesis, but

Professor Colin Renfrew describes the

upsurge in cave art in France and

Spain in the Paleolithic period as a “sort of creative explosion.”

Lord Renfrew of Kaimsthorn is Emeritus Disney Professor of Archaeology

at University of Cambridge and director of the McDonald Institute for

Archaeological Research there. Jointly with Templeton Research Fellow

Dr. Iain Morley, he is leading the investigation under the Foundation’s

program “Roots of Spirituality.” The work being done was already envisioned

when a Templeton Humble Approach symposium, held in 2004 at Les Eyzies,

“the capital of prehistory” in the Dordogne in France, on the topic of

“Innovations in Material and Spiritual Cultures,” acted as the catalyst.

“That particular meeting came about as the result of a proposal from

within Templeton,” recalls Renfrew, “rather than my applying externally

for support and it was Mary Ann Meyers who put forward the suggestion.”

From this emerged the more ambitious “Roots of Spirituality” project

which concludes this year. Its objective was to examine the early emergence

of the spiritual on a worldwide and comparative basis, using the available

archaeological evidence.

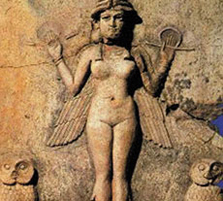

The project has two strands. The first, categorized as “Anthropomorphism:

the body” is concerned with early representation of the human body, especially

in three-dimensional form (figurines). The program convened an international

conference to discuss this topic: “Image and Imagination: Material Beginnings—The

Global Prehistory of Figurative Representation” in September 2005.

“We were able to look at every part of the world,” says Renfrew, “and

see how very often the first of these figurines for instance, if we’re

talking about human representations, emerge at the same time as the first

settled life, when people were living in villages for the first time,

which often correlates with the first practice of agriculture.”

But is it possible to look at a prehistoric figurine and confidently

ascribe a religious significance to it? “It’s not easy,” he says, “but

it is possible in one or two cases. A very good example would be the

so-called ‘Mistress of the Animals’ motif. This is a small figurine where

a woman is seated on a chair, which can reasonably be called a throne,

and the throne is supported by two leopards—that’s why it’s called the

‘Mistress of the Animals’ motif. Certainly, if one was talking about

later art, one would unhesitatingly regard this person as a goddess.

That is one of the earliest representations where it could be said this

must be a goddess figure.”

The other strand to the program is categorized as “Measuring the World.”

It too was the subject of an international conference, convened in September

2006, “Measuring the World and Beyond—The Archaeology of Early Quantification

and Cosmology.” “It really is fascinating,” observes Renfrew, “that in

some cultures in particular there is a preoccupation with units of measure,

both spatially in the layout of settlements and temporally in a preoccupation

with a precise calendar, and these things seem to be imbued with cosmic

significance.”

He cites the Maya as an example of this calendar preoccupation and, in

terms of spatial measurement with cosmic significance, the great city

of Teotihuacán in early Mexico “where there are enormous numbers of sacrifices

of human beings and animals buried in locations that are on precise alignments

on the main axis of the city.”

Both conferences produced books. The first, with the same title as the

event,

Image and Imagination, comprised the written contributions of

the nearly 30 participants and was published in November 2007. The contributions

to “Measuring the World” are likewise being published in book form, having

been accepted by Cambridge University Press. CUP will also publish a

third volume, entitled

Becoming Human: Innovation

in Material and Spiritual Cultures, based on the earlier meeting at Les Eyzies, which focuses on

the first homo sapiens and the “creative explosion” in the Upper Paleolithic

in France and Spain.

Considering that the work being done under “Roots of Spirituality” is

interdisciplinary and is drawing metaphysical conclusions from physical

artifacts, does it represent an extension of the frontiers of archaeology?

“I think we can say that it does,” responds Renfrew. He is insistent,

however, that researchers must not project backwards their knowledge

of religions in literate societies and then impose that interpretation

on earlier ages. “The keynote of our work has been to be critical of

claims that a particular finding represents some sort of spirituality.”

Taking all the evidence into account, is it possible we have underestimated

the metaphysical side of our remote ancestors? “I think it is very possible.”

here

and when did spirituality among humans have its beginning? Was there

a Big Bang moment for the metaphysical as well as the physical world?

There is insufficient data as yet to determine such a hypothesis, but

Professor Colin Renfrew describes the

here

and when did spirituality among humans have its beginning? Was there

a Big Bang moment for the metaphysical as well as the physical world?

There is insufficient data as yet to determine such a hypothesis, but

Professor Colin Renfrew describes the  upsurge in cave art in France and

Spain in the Paleolithic period as a “sort of creative explosion.”

upsurge in cave art in France and

Spain in the Paleolithic period as a “sort of creative explosion.”