od

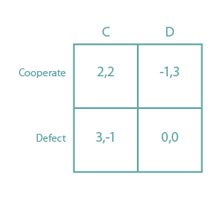

has raised the entire trajectory of evolution into existence,” says Martin

Nowak, “and this is one of the images that came out of our work.” He

is referring to the program “Evolution

and Theology of Cooperation” which,

with the help of a $2 million Templeton grant, he has been conducting

since 2005, investigating the phenomenon of cooperation within the evolutionary

process—more commonly regarded as competitive—and its implications for

theology.

Nowak, professor of biology and mathematics at Harvard University, has

been collaborating on the project with Sarah Coakley, the Edward Mallinckrodt

Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School, who has now accepted

an appointment at University of Cambridge in her native England. Nowak

attributes much of the success of the project to his colleague: “She

has managed to bring so many people to the table over these past years,

people from many different disciplines.”

The program has been strongly interdisciplinary, involving a cross-section

of theologians, philosophers, and scientists. The mathematics of evolutionary

game theory has been used to study the competition and cooperation of

individuals adopting various strategies and phenotypes. One such study

gained widespread publicity in early 2008. This was an experimental paper

called “Winners don’t punish” which demonstrated that individuals who

engage in costly punishment do not benefit from their behavior.

That paper was published in

Nature, as were several other essays produced

by the program group, including some that made the cover of that publication.

A volume is also in train. “At the moment we are writing a book,” reports

Nowak, “which has contributions from all those people who were involved

in the program and it will be ready in the second half of 2008.”

The numbers involved in the program increased to an unforeseen extent

as it progressed. Up to nine post-doctoral scholars and other participants

became involved, including some not funded by the Foundation. “Somehow

they were drawn in and they found it so exciting that they wanted to

contribute,” says Nowak. One designed a game theoretical experiment that

Sarah Coakley employed among the parishioners in her local church, testing

specifically religious motivations.

The project’s Visiting Scholars program was also a success. “We have

had a number of Visiting Scholars and some stayed for a year, for example

Philip Clayton (an expert on science and religion) and Timothy Jackson

(an ethicist), and others stayed for a shorter time.” Nowak believes

they injected fresh ideas into the discussions and there were always

visiting professors present throughout the project. There were also regular

monthly seminars, involving people like John Hedley Brooke, from University

of Oxford, as well as a conference at which the contributors included

Philip Clayton, Ingraham Professor of Theology at Claremont School of

Theology, Jean Porter, John A. O’Brien Professor of Theology at the University

of Notre Dame, Ned Hall of the Harvard Philosophy Department, and a group

of younger philosophers of religion: Alex Pruss, Dean Zimmerman, and

Michael Rota.

As regards the central focus of the study, the relationship between God

and the evolutionary process, Nowak and Coakley’s ideas converged over

the three years on a position much influenced by the thought of Thomas

Aquinas, but subtly modified to embrace the insights of contemporary

evolutionary theory.

“It is very important to realize that God is not only creator,” insists

Nowak, “but both creator and sustainer. God is not somebody who sets

the process going initially and then just watches everything unfolding,

but instead God is necessary to will every single moment into existence.”

He relates the teachings of the early Doctors of the Church to modern

evolutionary insights: “If you take the notion of Saint Augustine that

God is atemporal, it means that God—beyond time—can anticipate the outcome

of this evolutionary process.”

Although game theory has played a leading role in the program’s research,

Nowak has recently discovered a critical deficiency in this methodology.

It arises in investigating what he regards as the biggest question in

this field: the motivation behind altruism. “True altruism is defined

in the most meaningful way by motive.” But he now realizes that motivation

is something that has not yet played a role in the game theoretical analysis

employed by his team, in which action is decisive and motive is left

unexplored.

“The question why do you want to help somebody makes a big difference

when you come to think about the philosophical implications of altruism

and what true altruism, in the theological sense, actually is.” Nowak

describes the phenomenon of helping somebody out of love for the individual

and of God as “the only possible true altruism.” His dilemma, in terms

of research, is that there is currently no game theoretical means of

investigating this question of motive, but he is now working towards

developing such a system. The collaboration with other members of the

ETC team has been crucial in this development.

This program has a contrarian approach, insofar as it highlights cooperation

as a significant element in the evolutionary process which has so often

been identified with competition. There is a similar vein of unconventionality

in its openness to the reconciliation of evolutionary concepts with traditional

Thomistic theology, as well as its employment of game theory in its research

and Nowak’s determination to harness that methodology to his investigations

into altruism.

od

has raised the entire trajectory of evolution into existence,” says Martin

Nowak, “and this is one of the images that came out of our work.” He

is referring to the program “Evolution

od

has raised the entire trajectory of evolution into existence,” says Martin

Nowak, “and this is one of the images that came out of our work.” He

is referring to the program “Evolution  and Theology of Cooperation” which,

with the help of a $2 million Templeton grant, he has been conducting

since 2005, investigating the phenomenon of cooperation within the evolutionary

process—more commonly regarded as competitive—and its implications for

theology.

and Theology of Cooperation” which,

with the help of a $2 million Templeton grant, he has been conducting

since 2005, investigating the phenomenon of cooperation within the evolutionary

process—more commonly regarded as competitive—and its implications for

theology.